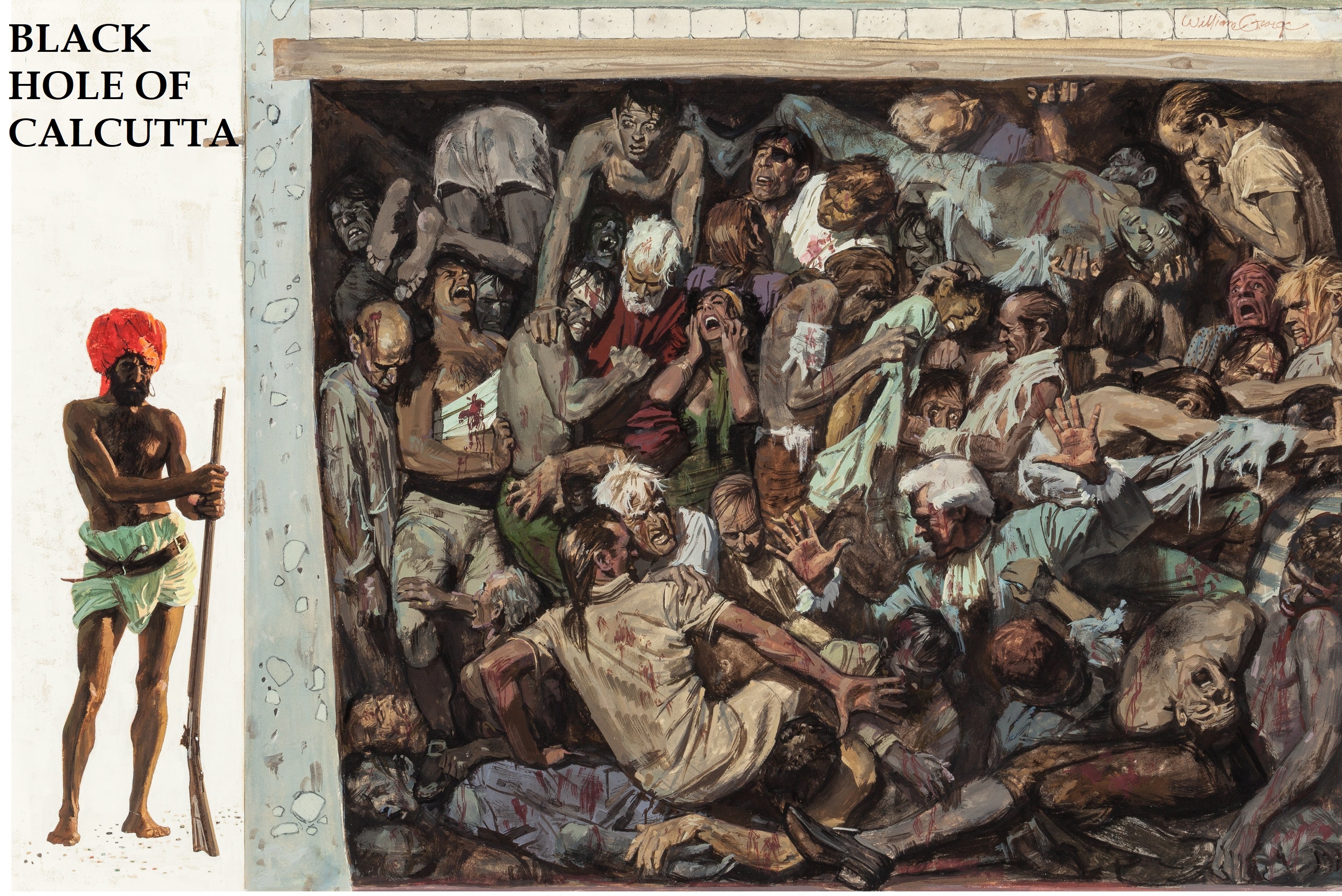

The Black Hole of Calcutta 1756

Posted by Timothy Roger Barrett - copyright on 3rd Jan 2015

……………………

Within the time of men who still live, the Black Hole was torn down and thrown away as carelessly as if its bricks were common clay, not ingots of historic gold. There is no accounting for human beings.

Mark Twain

……………………

The Siege

In the mid 18th Century, Bengal was ruled by the firm hand of a ruthless and cunning leader: Ali VardiKhan. Once, when troubled by various Maratha incursions into his territory, he invited their commander Bhaskar Pandit to peace talks, which Ali VardiKhan and all his leading commanders duly attended.

A productive dialogue ensued and negotiations were going well - until that is, a mob of Bengali soldiers sprang from behind the curtains, hacking, stabbing, slashing and chopping their way through the high ranking peace delegation- leaving nothing but a messy pile of noble corpses in the summit room. A contemporary historian remarked bitterly: ‘The annals of Indostan scarcely afford an example of such treacherous atrocity, and none of which persons of such distinction were the actors.’

Ali VardiKhan was certainly not a man not to be crossed, although he harboured a curios affection for his debauched grandson (who was also his grand nephew), Mirza Mahmood, a tyrant (or hero) known to history by his title of Sirajud Dowla[1] (Lamp of the State).

Mirza had at one time become impatient to succeed his grandfather. To rectify this apparent injustice he turned to open rebellion and besieged Patnain Bihar. His co-conspirators were quickly killed off in the struggle and with characteristic lack of determination, Sirajquickly surrendered. Ali VardiKhan unequivocally forgave his errant grandson and in 1753 he officially made him the successor to the throne, creating no small amount of division in the family and the royal court. In 1778, Robert Orme wrote of this relationship:

Mirza Mahmud [Siraj], a youth of seventeen years, had discovered the most vicious propensities, at an age when only follies are expected from princes. But the great affection which Allaverdy [Ali Vardi] had borne to the father was transferred to this son, whom he had for some years bred in his own palace; where instead of correcting the evil dispositions of his nature, he suffered them to increase by overweening indulgence: born without compassion, it was one of the amusements of Mirza Mahmud's childhood to torture birds and animals; and, taught by his minions to regard himself as of a superior order of being, his natural cruelty, hardened by habit, rendered him as insensible to the sufferings of his own species as of the brute creation [animals]: in conception he was not slow, but absurd; obstinate, sullen, and impatient of contradiction; but notwithstanding this insolent contempt of mankind, innate cowardice, the confusion of his ideas rendered him suspicious of all those who approached him, excepting his favourites, who were buffoons and profligate men, raised from menial servants to be his companions: with these he lived in every kind of intemperance and debauchery, and more especially in drinking spiritous liquors to an excess, which inflamed his passions and impaired the little understanding with which he was born. He had, however, cunning enough to carry himself with much demureness in the presence of Allaverdy, whom no one ventured to inform of his real character; for in despotic states the sovereign is always the last to hear what it concerns him most to know.[2]

Although conveniently proclaimed as a freedom fighter in modern India, historians of the period, both British, Frenchand Indian, tell us that Sirajwas nothing but an opportunistic degenerate braggart.

Two contemporary Muslimhistorians speak of him. Ghulam Husain Salim, author of Riyaz-us-Salatin, wrote:

Owing to Sirajud Dowla’s harshness of temper and indulgence, fear and terror had settled on the hearts of everyone to such an extent that no one among his generals of the army or the noblemen of the city was free from anxiety. Amongst his officers, whoever went to wait on Sirajud Dowla despaired of life and honour, and whoever returned without being disgraced and ill-treated offered thanks to God. Sirajud Dowla treated all the noblemen and generals of Mahabat Jang [Ali VardiKhan] with ridicule and drollery, and bestowed on each some contemptuous nickname that ill-suited any of them. And whatever harsh expressions and abusive epithet came to his lips, Sirajud Dowla uttered them unhesitatingly in the face of everyone, and no one had the boldness to breath freely in his presence.

Another great Muslimhistorian of the period, Ghulam Husain Tabatabaihad this to say about him:

Making no distinction between vice and virtue, he carried defilement wherever he went, and, like a man alienated in his mind, he made the house of men and women of distinction the scenes of his depravity, without minding either rank or station. In a little time he became detested as Pharaoh, and people on meeting him by chance used to say, ‘God save us from him!'

A Frenchman and ally in his court, by the name of Law, gives the following insightful account of this Bengali Caligula:

He was often seen, in the season when the river overflows, causing ferry boats to be upset or sunk, in order to have the cruel pleasure of seeing the confusion of a hundred people at a time, men, women, of whom many were sure to perish.

When Sirajwas not busy sinking ferry boats and hounding his nobles, his other pleasures included cutting open the bellies of women in advance stages of pregnancy to observe how the squirming child lay in the womb and kidnapping beautiful Hindu maidens who were accustomed to bathe on the banks of the river Ganges. This he would do with the aid of spies, who were paid to inform him of the whereabouts of the prettiest females. Even before he attained the throne, the British were weary of him, refusing him entry into their homes lest he break the furniture! Forget the patriotic Indian jingoism - Sirajwas a monster, a vicious base degenerate pervert.

Ali VardiKhan’s long life drew to a close at Murshidabadin April 1756. A few days before his death his death the old Nawab (ruler) is said to have solemnly told his heir, 'keep in view the power the European nations have in the country. Think not to weaken all three altogether. The power of the English is great. Reduce them first; the others will give you little trouble when you have reduced them. Suffer them not to have fortifications or soldiers.'

Ali VardiKhan’s

dyeing wishes were at odds with his previously recorded views on Europeans.

Perhaps bitter experience had hardened his attitude or the trauma of lying on

his deathbed had somehow clouded his judgement.A Muslimhistorian

asserted that Ali Vardihad at

one time recognised the formidable greatness of England, especially its maritime

capabilities. For example, upon hearing that one of his generals was advocating

an attack on Calcutta, he is said to have replied, 'Look at yonder plain

covered with grass should you set fire to it there would be no stopping its

progress, and who is the man then who shall put out a fire that shall break

forth at sea and from thence come out upon land? Beware of lending an ear to

such proposals again, for they will produce nothing but evil.'

The truth is probably that in the last years of his life, Ali Vardimodified his views, and while quite aware ofthe advantages of Europeans trading in his province, desired that they should confine themselves to trading, and not import their Western quarrels into Bengal and become too militaristic; and he accordingly advised his successor to enforce this, knowing that Sirajwas going to be less artful at keeping them in check than he, but he probably did not intend it as an instantaneous call to arms.

Tempted by the vast wealth which rumour credited the English of having accumulated, Siraj, the new Nawab very soon found pretexts for quarrelling with the East India Company. They had lately refused to give up a fugitive who took refuge in Calcutta, whom he accused of absconding with revenue that had not been accounted for. The English had also quite stupidly neglected to send the customary congratulations and present to the new ruler. This gave rise to a suspicion that the English presumed to look with disapproval upon Siraj’s elevation, and were disposed to favour some of the other aspirant.

It so happened that about this time the English were commencing to repair their fortifications at Calcutta in expectation of a fight with the French;[3] this news came to the ears of the Nawab just as he was setting up a large army to thrashhis cousin and rival, the Raja of Purnea.

He at once sent orders that the repairs should be discontinued. English protests from Calcutta reached him in Rajmehal. The Nawab was told that he had been misinformed about the English building a wall round the town, that they had not excavated any ditch[4] since the invasion of the Marathas, at which time such a work was executed at the request of the Indian inhabitants, and with the knowledge and approval of Ali Vardi.They added that in the last war between England and France, the French had taken the English settlement atMadras- contrary to the neutrality expected in the Mogul's dominions and that by preparing a line of guns along the river they were readying themselves for a similar act of Gallic aggression against Calcutta.One source states that the English offered to fill up the ditch with the heads of Muslims!

Whatever the reply, it was sufficiently irritating for him to put the Purnea expedition aside, and direct his army to Murshidabad, sending forward a large detachment of 3,000 to lay siege to the Company's modest fort at Kasimbazar, close to his capital.

Thisfort was a shambles, and as much a threat to the Nabob's power and authority as a girls' school. Orme notes that 'none of the cannon were above nine pounders, most were honey-combed, many of the carriages decayed, and the ammunition did not exceed 600 charges.' The garrison consisted of22 Europeans, mostly Dutchmen, and 20 Topasses[5] (Christian Indians, often with mixed Portuguese blood). The Company's chief officer at Kasimbazar, Mr. Watts, 'surrounded by menaces', signed a document of surrender (4th June).

The Nawab had ordered that all the warehouses were to be sealed up and guarded, but instead his unruly troops looted most of what they found. Their attentions were then drawn to the prisoners, who they taunted to such an extent that the chief of the small garrison, Ensign Elliot, shot himself through the head.

The easy and ample success of this first act of hostility, put the Nawab in a triumphant and happy mood.There seemed to be nothing to prevent him from driving the foreigners out of Calcutta and capturing and plundering their settlement, which was thought to be the most opulent city in the Empire even though, for the large part, it was nothing more than an assemblage of wretched huts, clustered around a dilapidated fort with but seventy houses occupied by Europeans.

Wishing to act with haste and decisive force before they could proceed further with their defences and before the season of the southwest monsoon was advanced enough to bring the British assistance by sea, he set out for Calcutta by a series of forced marches.Adding to their haste was the fear of daily-expected rains that would have brought misery to the rank and file, and greatly hampered progress.

The number of the forces constituting his army have been estimated at around30,000 on foot, 20,000 horse, 400 trained elephants, and 80 pieces of canon, some of them being light guns taken at Kasimbazar[6]. About 20,000 of his troops were adequately armed with muskets, matchlocks, and wall pieces, the rest with lances, swords, bows and arrows, etc. Fully 40,000 followers and bandits of all sorts are said to have attended the army to take part in the plunder of Calcutta. So strong was the confidence in the success of the expedition.

In seven days this host covered the distance between Murshidabadand Hugli. The immediate crossing of the river was effected from Chandernagorein an immense fleet of boats assembled there for that purpose.In this endeavour to oust the British from Bengal Sirajud Dowla demanded submission, and assistance from the Frenchand Dutchestablishments thereabouts, they pleaded, however, that theirs was merely a peaceful trading occupation, and appeased him with promises of money.[7]

Meanwhile, Calcutta waspreparing itselffor the approaching visitation. By the 1st of June they knew that Kasimbazarwas threatened, but not till the 7thdid authentic information reach them that it had fallen without striking a blow, and that an immediate descent upon the chief settlement had been proposed. 'When the Nawab’s intention of marching on Calcutta was known, it was felt time,' candidly writes the Adjutant-General, 'to enquire into the state of defence and the garrison, neglected for so many years, and the managers of it, lulled in so infatuate a security, that every rupee expended in military services was esteemed so much loss to the company.'

The Company's fort at Calcutta was built at the end of the 17th Century. When permission was obtained for enclosing it, it was fortified, optimistically called a fort and named after William III.This fortress, the object of Siraj's ire, had four bastions; the outer walls were tough but barely four feet thick and were about 18 feet high. The walkways behind the battlements, upon which the men stood,were merely the roofs of the chambers and warehouses below. Worse still, large windows were in several places opened through the walls for the ventilation of the rooms abutting them. There is no surer proof of the peaceable nature of the British in Bengal at this time than the condition of their principle stronghold.

This so-called fort was unprotected by any encompassing ditch or moat, and was actually overlooked by several nearby English houses. Other homes which lurked under its shadow, had attached gardens enclosed in sturdy walls making them ideal cover and mustering points for the attackers. Towering above the fort, and adjacent to it, stood Calcutta's church (built in 1715). Finally, the whole of the defensive work had been allowed to fall into such a state of bad repair, as to be quite unfit to resist any well-organised attack. The walls and terraces were so shaky that it was not thought prudent to allow cannon to sit upon them! The defensive fire was mainly restricted to that from the bastions and gate. The defences proved the most insubstantial on the south side, as there, for the purpose of providing increased accommodation, some warehouses called 'the new go-downs' had been built a few years before and were actually leaning against the south wall and obstructed flanking fire from two of the turrets. As small compensation, the roof of the new warehouse was made just about strong enough to carry a battery of light guns.

The garrison consisted of only 180 largely untrained men, only a third of whom were Europeans. They were under five officers; of these Captain Buchananwas the only one with campaign experience. To add to the fighting strength, the European and Armenian inhabitants were enrolled as militia; most of these had never handled firearms before. Indian employees of the Company were also enlisted in large numbers to defend Calcutta - and deserted at the earliest opportunity.

Ill adapted as the fort was for defence(it was in reality a lesser stronghold than at Kasimbazar) it was still the best hope of holding out till an escape could be effected by the river, and it was the only hope for concentrating the garrison. The Europeans got to work demolishing as many of the adjacent houses as possible. Unfortunately, the Fort was still pronounced incapable of stopping a determined enemy by the many counsellors who had a voice in the matter.

As for their modes of defence, the Victorian historian, H. E. Busteedwrote: 'To meet the enemy in the principal streets and avenues, and at improvised outposts; no better scheme of spreading out and wasting the untrained and insufficient defending force could have been devised.' Holwell called the preparations for defence, a 'tragedy of errors... which were all in the wrong direction.' It is clear that Calcutta had little understanding of the malignant deluge that was about burst upon it. One writer (Hastings' MSS.) records, 'The military were very urgent for demolishing all the houses, knowing that if once the enemy got possession of the white houses, there would be no standing on the factory walls. However, the pulling the houses was a thing they would not think of, not knowing whether the Company would reimburse the money they cost.' A certain Captain Grantsays, on the same subject:

It may be justly asked, why we did not propose the only method, that as I thought then, and do now, could give us the least chance of defending the place in case of a vigorous attack - the demolition of all the houses adjacent to the Fort, and surrounding it with a ditch? But so little credit was then given, and even to the very last day, the Nawab would venture to attack us or offer to force our lines, that it occasioned a general grumbling and discontent to leave any of the European houses without them. ...And should it be proposed by any person to demolish as many houses as should be necessary to make the fort defensible, his opinion would have been thought pusillanimous and ridiculous.

'Entrenchments,' notes a junior employee of the Company 'were begun to be thrown up across the park, and a ravelin to defend the front gate of the factory, but [we] had no time to finish them.' A large number of Indian peons occupied posts at an important defensive work which went by the name of 'the Mahratta Ditch', but in no time at all these men went over to the enemy - and with them the only attempt to defend this important defensive work.

The Frenchand Dutchtreated English requests for help, with considerable indifference. Of the former, an indignant youngCivilian[8]writes:

We wrote... a very genteel letter [to the French], thanking them for their offer of assistance, and as we were in very great want of ammunition, requested they would spare us a quantity of powder and shot.When the Nawab was near Calcutta, the Frenchmen put off their grimace, assuring us of the impossibility of complying with our demand, as they might provoke the Nawab by it. However, when the Nawab demanded supplies of powder from them soon after, they would then find sufficient to give him 150 barrels, and could connive also at the desertion of near 30 men, which joined the Nawab’s army before the taking of Calcutta, and commanded the artillery under Monsieur St. Jacque.

Captain Grant, the Adjutant-General, also mentions the presence of Europeans with Siraj's army at Calcutta. Grant says they learnt from prisonerstaken whilst the attack was going on, that the enemy had with them '25 Europeans and 80 Chittygong Fringeys' [Literally, ‘foreigners from Chittagong’, now in southern Bangladesh] under the command of one who styled himself Le Marquis de St. Jacque, a French renegard [sic], for the management of their artillery.' The English however also had a French lieutenant fighting on their side, a Monsieur Le Beaume, who Grant says, 'was a Frenchofficer and left Chandernagore[9]on a point of honour.' He fought bravely and managed to escape the Black Hole.

Hostilities commenced even before the enemy arrived. On the 13tha very suspicious letter was intercepted on its way to Omichund, the settlement's wealthiest Indian resident. He was immediately put under house arrest. His brother-in-law, Hazarimull, who had the chief management of his household affairs, concealed himself in the ladies' quarters. A band of troops went in after him but were resisted by three hundred of Omichund's loyal servants who had armed themselves and put up a spirited and violent defence of the household during the course of which the house caught fire. In the midst of this insurrection, the chief servant entered into the women's quarters, and fearing for the honour of his master's women, massacred thirteen of them, and then stabbed himself - but was overpowered by British troops before he could complete his suicide.

The advance guard of Siraj's army did not bother to reconnoitre the city nor did it gather intelligence, instead the eager troops charged like enraged bulls towards the Maratha Ditch: an incomplete defensive work that they could safely have walked around. The redoubt in this area was held by 20 Europeans and Indian troops who gave the attackers a warm reception. Thirty more Europeans and a few cannon sallied forth from Fort William to reinforce the vastly outnumbered defensive line - who bravely held their ground and kept up a steady fire, whilst four thousand of the enemy took up positions in the thickets. At midnight the rattle of Indian musketry and the roar of their cannon fell silent, for Siraj's army had settled down to an evening meal and was making themselves comfortable for a night's sleep.

As the evening dragged on, Ensign Prichard, who had previous experience in fighting Indians, assured his incredulous colleagues that the enemy were asleep, he then led the small force into the thickets, where they set about bludgeoning, bayoneting and shooting their sleeping enemies, their chief target however being the canons that had caused them so much grief during the day, which they seized and disabled. The successful raiding party then withdrew, without a single casualty.

One of Omichund's battered servants arrived into the enemy camp and warned Sirajthat they were attacking the city in the wrong place. At last, finding that they could enter the city freely by walking around the ditch, from which they had been so violently repulsed, they entered the town through Dum Dum(now a suburb of Calcutta) and on the morning of the 18th swarmed all around the town, plundering and setting fire to every bazaar in their way and looting the city. At this point another party sallied forth from the fort and evicted many of the marauders. The English also set fire to as many bazaars as they could to deny shelter and stores to the enemy:- 'when many of our people being detected plundering, they were instantly punished with decapitation.' The party returned with prisoners who after interrogation informed them of an imminent an all-out attack on the redoubt, during which they would have been assailed from both sides. Confronted with this dire news, Prichard and his bellicose troops were withdrawn back into the fort.

John Zephaniah Holwell was of Irlsh extraction. He assumed the office of

Zamindar (tax collector and local judge) in 1752 and remained in the post

till 1756 His first visit to Calcutta was as a sergeant's mate of an East Indiaman

in 1732. In 1736 he was appointed as one of the aldermen of the Mayor's Court,

and in 1748 he returned to Europe. He prepared a plan for reforming abuses

in connection with the Zamindar's Cutchery (office) and submitted the same

to the Court of Directors, who were. so pleased with him that they made him

the permanent Zernindar of Calcutta and twelfth in the Council.

(Picture: Sir J. Reynolds)

On the 18th, the English issued orders that no quarter was to be given, as the prisons were already full, and naturally enough they understood that the enemy would similarly retaliate. Most of the day's combat occurred at the outpost which first received the enemy attacked from the east. The battery, opposite the Mayor's Court, was partly held by a detachment of the militia commanded by Holwell. It was in a very exposed position and doggedly defended. So heavy was the fire on it from the points of vantage nearby, that only the men necessary to work the guns were allowed to remain in it; the rest got under cover within the Court House and had the grim task of taking over from those who were gunned down.

The battery to the north was also attacked, but here the enemy had few advantages and the attackers found themselves advancing in close order up a narrow street. The first volley from the English cannon was horrifically effective. Today we can have little conception of the shocking carnage of an 18th Century battle: of the damage caused by a solid cannon ball hurtling its way though ranks of tightly packed men, knocking them over like skittles - a scene never adequately recreated in modern cinematography.Men were literally pulverised by the solid projectiles, brains, shards of wet bone and intestines were thrown around like so much debris. The wounded, who were deposited in heaps, were given nothing to alleviate the agonies of broken ribs, skulls and crushed bones. This awful spectacle was too much to bear for the disorganised enemy, who rather than press home the advance and overwhelm the enemy, immediately took cover in the side streets, rendering ineffective the sacrifice of their colleagues.

From these side streets small groups would appear to take pot shots at the English sheltered behind their sandbags and embrasures - having satisfied themselves with this random fire, the enemy would then furtively run for cover. The vexed English came up with the idea of taking the canon to this concealed enemy. A group of men wheeling a field piece were then detached to drive the enemy out of the alleyways: seeking what would nowadays be called a 'target rich environment'. As they wheeled their gun around the corner, Siraj's shocked troops were given another disastrous dose of English lead - the enemy fled wildly from the detachment, who, elated by their success, pursued them further into the winding alleyways, blasting any place where the enemy chose to hide, and in doing so lost sight of the main battery. Siraj's troops, taking advantage of this error, returned through the narrow back streets to cut off their retreat - the English turned their cannon upon them, and as the weapon blasted another wave of destruction through their tightly packed ranks, yet again the enemy lost their nerve and ran. The few that got close enough to the band of Englishmen to engage with them, were shot with muskets or cut down with sword or bayonet. It had been a close call for the foolhardy party, and they decided to return to the safety of the fortified position before a more successful attempt to apprehend them was organised.

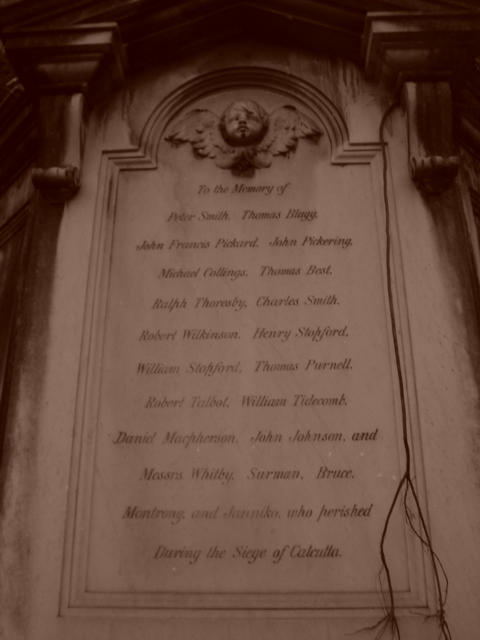

Black Hole of Calcutta Memorial, photographed by the author in 2004

By now the Indian

troops in this area had been badly mauled, and decided to try their luck in the

fight against Holwell's eastern battery, which being in a more

exposed position was taking a severe hammering. At

About four o'clock in the afternoon, a multitude of the enemy forced the palisade at the farther end of the Rope Walk[10], although defended by a sergeant and twenty men; and rushed down the walk with so much impetuosity towards the eastern battery, that the gunners had scarcely time to turn one of the eighteen pounders against them; however, the first discharge of grape shotchecked, and a few more drove them to seek shelter in the covers at hand; but many of them joined those who were in the houses from which the fire increased so much, that at five o'clock, the military officer who commanded the battery, sent Mr. Holwell, who acted as a lieutenant under him, to represent to the governor the impossibility of maintaining this post any longer, unless it was immediately reinforced with cannon and men, sufficient to drive the enemy out of the houses: but before Mr. Holwellreturned, Captain Claytonwas preparing to retreat, having already spiked up two eighteen pounders and one of the field pieces; and the whole detachment soon after marched into the fort with the other. They were scarcely arrived before the enemy took possession of the battery, and expressed their joy by excessive shouts.

The retreat into the fort was messy and disorganised. Two fortified houses remained, both of which had defended the flanks of the eastern battery, these were still held by the English and in imminent danger of being cut off. In one of the houses, a sergeant and twelve men fled to the southern battery before the enemy had gathered in any significant numbers. The other house was occupied by alieutenant and nine of the militia, all of whom were young men in the mercantile service, they were given no warning that the sergeant was about to leave his post and seeing that the houses were being surrounded they endeavoured to also get away. Forming into a compact body they came out firing. Most of them made it, apart from two young men called Smith and Wilkenson. These were separated from the rest, immediately intercepted and called upon to surrender. Smith refused and is said to have cut down five men[11] before surrendering, after which Wilkenson handed over his weapon, and was immediately 'cut to pieces'.

In addition to the regular garrison and militia, who with their families took to the safety of the old fort, there were also about 3,000 'unnecessary people,' labelled as 'black Christians, Portuguese, slaves, &c.' Their presence only added to the panic and chaos within. The Adjutant-General records:

Provisions had been laid in, but proper persons had not been appointed to look after them; and the general desertion of the black fellows, amongst whom were all the cooks, left us to starve in the midst of plenty. All the men at the outposts had no refreshments for 24 hours, which occasioned constant complaint and grumbling all this night.We were so abandoned by all sorts of labourers, that we could not get carried up on the ramparts cotton bales and sand-bags for the parapets of the bastion, which were very low and the embrasures so wide that they hardly afforded any shelter.

The Batteries had been so much relied upon as the best defences of the settlement, that the desertion of them on the very first day of the engagement created much consternation and uproar, especially amongst the non-combatants, who expected no quarter from the besieging enemy. Only twenty Lascars(Indian Sailors) remained to man the cannon, and all of the Company's Indian troops had deserted. The Armeniansand Portuguese were said to have been 'stupefied with fear'. The situation was going from bad to worse, as by now the enemy had repaired many of the captured cannons and were turning them against the walls.

At this point all order broke down and there followed acts of great cowardice and insane valour. When the enemy started climbing upon the walls of the adjacent warehouse, the governor ordered a roll of drums to signal the general alarm. The urgent signal was repeated three times and ignored on every occasion.The enemy however was unnerved by the raucous drumming and presuming that a tightly packed gang of redcoats would at any moment open fire, with this in mind they decided to remove themselves from the exposed roof and beat an unwarranted retreat.

Late in the evening of the 18th,many of the women and children were put aboard ships. Two members of the Council, both acting as officers of militia(Messrs. Manningham and Frankland) embarked with the ladies, having volunteered themselves for this duty. A young civilian wryly remarked: 'our colonel and lieutenant-colonel of militia preferred entering the list among the number of women rather then defend the Company's and their own property. Accordingly they went offwith them, and though several messages were sent them to attend council if they did not choose to fight, still no persuasion could avail.'

The boats were filled with everything that could be carried and in the mad scramble, several of these vessels sank and many of those who were huddled on board were drowned whilst some managed to swim to a far bank and were either taken prisoner or simply massacred. As the escaping vessels breezed past, Siraj's troops fired flaming arrows at them in hope of setting them ablaze.

In this hour of trepidation, many of the English militia, seeing the vessels under sail became terrified of losing their last chance of escape. The governor, who was utterly unversed in military affairs, had up to this point shown no aversion in exposing himself to danger. Earlier that morning he had braved bullets and arrows and visited the ramparts asby daybreak the English were firing with wall-pieces and small arms from every breach and corner. The enemy, now appearing in immense swarms all round the fort,struck enormous fear into many, expecting that at any moment the place would be overwhelmed by this bloodthirsty multitude, who despite having taken thousands of casualties, showed no sign of giving up. A Captain by the name of Grantsaid that the artillery from the fort during the early morning did 'terrible execution' amongst the crowded enemy, but did not dampen the amount of incoming fire.

Sometime later an alarm was raised, indicating that the enemy were at the gates. To his credit, the governor was one of the first on the scene. He ordered two cannons to be pointed at the gateway, but found nobody willing to obey him. Meanwhile the enemy contented themselves with launching volleys of flaming arrows into the fort - fortunately, most were too busy plundering the city to bother with the object of their mission. Not long after this uninspiring episode, word came to him that the remaining gunpowder was damp and out of service. Although he was dismayed by this information, he refrained from divulging it- it was obviously the final straw. Two boats remained at the wharf and he ran for them. Busteed notes: 'Soon occurred the incident which obliges us to look back on some portion of the defence of Calcutta with humiliation. As this is the first and only instance in the history of British India, in which those bearing the names of Englishmen, and placed in a conspicuous position in a time of war, set an example of cowardice, desertion and inhumanity...' The Adjutant-General gives us a vivid account of the stampede to the last boats and of the governor's flight:

Between 10 and

Black Hole of Calcutta memorial, in 2004 (picture taken by the author)

Upon the Governor going off, several muskets were fired at him, but as the junior civilian lamented: none were lucky enough hit. Grose in his Voyage to the East Indies stated that Drake pleaded that he was a Quaker and as a man of peace, needed to hurry away from a scene of bloodshed. John Cooke, a 'Bengal civilian', gave an enlightening account in evidence he gave before a Parliamentary Committee:

Signals were now thrown out from every part of the Fort for the ships to come again to their station, in hopes they would have reflected (after the first impulse of their panic was over) how cruel, as well as shameful, it was to leave their countrymen to the mercy of a barbarous enemy; and for that reason we made no doubt they would have attempted to cover the retreat of those left behind now they had secured their own; but we deceive ourselves, and was never a single effort made in the two days the Fort held out after their desertion to send a boat or vessel to bring off any part of the garrison. All the 19ththe enemy pushed on their attack with great vigour, and having possessed themselves of the church, not thirty or forty yards from the east curtain of the Fort, they galled the garrison in a terrible manner, and killed and wounded a prodigious number. In order to prevent this havoc as much as possible, we got up a quantity of broadcloth in bales with which we made traverses along the curtains and bastions; we fixed up likewise some bales of cotton against the parapets (which were very thin and of brick only) to resist the cannon balls, and did everything in our power to baffle their attempt and hold out, if possible, till the Prince George (a company's ship employed in the country) could drop down low enough to give us an opportunity of getting on board... The enemy suspended their attack as usual when it grew dark; but the night was not less dreadful on that account. The Company's house and the marine yard were now in flames, and exhibited a spectacle of unspeakable terror. We were surrounded on all sides by the Nawab’s forces which made a retreat by land impracticable; and we had not even the shadow of a prospect to effect a retreat by water after the Prince George ran aground. On the first appearance of dawn on the 20thJune, the besiegers renewed their cannonading- they pushed the siege this morning with much more warmth and vigour than ever they had done...

There was another vessel aside from thePrince Georgethat could have rendered assistance, the aforementioned Dodalay. Captain Young, the vessel's commander said afterwards, he did not attempt a rescue because it was too dangerous! The civilian's manuscript adds that this vessel would not even give a cable and anchor to those stranded on the Prince George so they could get off the stricken ship. Supporting this refusal on the grounds that bad weather was at hand and all the gear would have been needed for herself. Holwellbitterly comments:

A single sloop or boat sent up on the night of the 19thmight have hailed us from the bastions without risk, even if the place had been in possession of the enemy, the contrary of which they would have been ascertained of, and the fleet might have moved up that night. This motion would have put fresh spirits into us and given dismay to the enemy already not a little disheartened by the numbers slain in the day when dislodged from the houses round us. Had the ships moved up, and our forces reunited and part of the ammunition on board them been disembarked for the service of the Fort, the Suba might at least have been obliged to retreat with his army, or at the most, the effects might have been shipped off on the 20theven in the face of the enemy, without their having power to obstruct it and a general retreat made of the whole garrison, as glorious to ourselves, all circumstances considered, as the victory would have been.

By

For over two hours (after the attack on the northern wall was beaten off) the enemy disappeared, but at approximately 4 p.m. Holwellwas informed that a man was advancing with a flag, and calling for a cease fire - offering quarter in case of surrender. The English responded by hoisting a flag of truce. Shortly afterwards, taking advantage of the lull in musketry: 'multitudes of the enemy came out of their hiding-places round us, and flocked under the walls.'

Holwelltook to the battlements to parley with the enemy, one of Siraj's officers called out that the Suba was there, and that he wished for the Union Jack to be lowered and for the fort to surrender. Before a reply had left Holwell's lips, a shot rang out and Mr. Baillie, who was standing next to him, fell wounded, which was followed by a general rush on the eastern gate.

Holwell, brought a cannon to bear on the gate, upon which the enemy withdrew and the flag of truce was taken down. Holwellthen ordered a 'general discharge of our cannon and small arms: 'a desperate call to arms which was not eagerly taken up. At this moment word came to Holwellfrom Ensign Walcot that the western gate had been forced open by their own people in an act of betrayal. One account has it that some of the defenders had made an attempt to escape during the brief truce,'under cover of prodigious thick smoke.'

Holwellrushed to where Captain Buchananwas in charge, and found the enemy's colours already planted there. 'I asked him how he could suffer it; he replied he found further resistance was in vain.' All around him Siraj's men were scaling the walls with bamboo ladders - the game was up.

The Indian troops refrained from slaughtering the Europeans. Busteed correctly notes: 'This unexpected forbearance should be remembered to the credit of the enemy, to whom 'no quarter' had been given, and from whom the defenders acknowledge they could not hope for any. The enemy began looting instead of killing, stripping the gentlemen of their buckles, watches, money and gold. Holwellhanded over his pistols to the first native officer whom he saw coming towards him, and was told to instantly order the British colours to be cut down. This was one request that he refused to grant - saying that, as masters of the Fort, they might order it themselves. He was then requested to hand over his sword, but again refused to do so, unless in the presence of the Suba. To formally effect this surrender Holwellwas led along the ramparts to be presented before Siraj. Holwellrespectfully greeted him from the rampart, and then delivered his sword. Holwellhad three subsequent interviews with him that evening. Says Holwell:

He expressed much resentment at our presumption in defending the fort against his army with so few men, asked why I did not run away with my governor, &c., &c., and seemed much disappointed and dissatisfied with the sum found in the treasury; asked me many questions on this subject, and on the conclusion he assured me on the word of a soldier that no harm should come to me, which he repeated more than once.

In some brief histories of the Raj, Calcutta is described as having fallen easily. This is probably largely the fault of the eminent 19thCentury historianMacaulaywho stated that 'the Fort was taken after a feeble resistance,' a statement that is true enough when referring to the regular garrison but ignores the latter stages of the struggle maintained predominantly by the militia.

Some early British writers may be accused of aggrandisement and for obvious reasons. It is therefore proper to quote a contemporary Muslimwriter, Gholam Hussien, who pays tribute to Holwelland his fellow-defenders:

Mr. Drake finding that matters went hard with him, abandoned everything, and fled without so much as giving notice to his countrymen. He took shelter on board of a ship, and with a small number of friends and principal persons he disappeared at once. Those that remained, finding themselves abandoned by their chief, concluded their case must be desperate; yet most of them were impressed with such a sense of honour, that, preferring death to life, they fought it out till their powder and ball falling at last, they bravely drank up the bitter cup of death; some others, seized by the claws of destiny, were made prisoners.

The victory was not accompanied by universal acclaim in Bengal. The region's Hindus, who had been much troubled by Siraj's lunacy and often laboured under a discriminatory regime, had hoped that Sirajwould ruin himself in his fight against the English and many were profoundly disappointed by Calcutta's fall, which they undoubtedly feared would add to the tyrant's arrogance and vanity. After his victory the Hindus ire turned against the 'incompetent' Europeans. One Frenchobserver wrote: 'The country people here about call the Europeans Banchots,[12] ie., cowards and poltroons.'

As an indication as to how high Indian bodies piled up around Fort William: after the battle, Holwell, (in his first report on the matter written to the BombayGovernment in July from Murshidabad) says: 'of the enemy we killed first and last, by their own confession, 5,000 of their troops and 80 Jamedars and officers of consequence, exclusive of their wounded.' Even if this is only half true, or even if it has been inflated by three or four times - it is still a damning indictment of the leadership, a military ignoramus and non-entity such as Sirajud Dowla who could so incompetently lead eager and well-motivated troops into such a disproportionate slaughter.

At this juncture we come to the infamous Black Hole incident. I do not wish to take the reader down a well trodden path and simply tell my own version of the story, this I believe would contribute little to an overall understanding of the subject matter. I have therefore endeavoured to reprint most of Holwell's original testament regarding his sufferings in the Black Hole taken from Interesting Historical Events Relative to the Province of Bengal and the Empire of Indostan. (2 Parts, 1765 & 1767 ).

I think the modern reader will find Holwell's account to be exceptionally clear in its grammar and literary style - despite being almost 250 years old. The veracity of this gruesome narrative has become a highly contentious issue - as most 'politically correct' historians call Holwell a liar. Without doubt, they feel uncomfortable about Indians being portrayed as aggressors and perpetrators of atrocity, in short, the entire episode as told by Holwell deeply upsets well established and appealing stereotypical notions of Indians being the sole victims of atrocity. Moreover, to accept that the Black Hole incident did happen as per Holwell's account, concedes that the British forces under Sir Robert Clive another adequate excuse to fight Siraj. This is why the document remains, to this day, a real hot potato and this may explain why it is so rarely reproduced. It is sometimes erroneously stated that Holwell gives us the only account of the incident. This is not correct; it is not even the most important testament!

Secretary Cooke also survived the Black Hole, he became member of Council and afterwards - in England - gave evidence before the Parliamentary Committee of 1772, to which we are to believe he perjured himself, if we pay heed to the view of certain 20th Century historians. The sole female survivor, Mrs. Carey, was also informally interviewed regarding her experiences, during which she also confirmed Holwell’s account of the incident.[13] Critics of Holwell's story claim that he fabricated the story to aggrandise himself (something that we shall scrutinise more carefully later) yet they do not and can not explain why Cooke would have put himself in legal jeopardy to confirm Holwell's ‘fictitious’ account. If the basis of history is testimony, then I must contend that the entire tragedy is well accredited.

We enter into Holwell's discourse when he and approximately 146 others are about to be thrust into the dungeon by Indian troops who had just taken over Calcutta:

They ordered us all to rise and go into the barracks to the left of the court guard. The barracks, you may remember, have a wooden platform for the soldiers to sleep on, and are open to the west by arches and a small parapet wall, corresponding to the arches of the veranda without. In we went most readily, and were pleasing ourselves with the prospect of passing a comfortable night on the platform, little dreaming of the infernal apartment in reserve for us. For we were no sooner all within the barracks, than the guard advanced to the inner arches of the parapet-wall; and, with their muskets presented, ordered us to go into the room at the southernmost end of the barracks, commonly called the Black-Hole prison; whilst others from the Court of Guard, with clubs drawn and scimitars, pressed upon those of us next to them. This stroke was so sudden, so unexpected, and the throng and pressure so great upon us next the door of the Black-Hole prison, there was no resisting it; but like one agitated wave impelling another, we were obliged to give way and enter; the rest followed like a torrent, few amongst us, the soldiers excepted, having the least idea of the dimensions or nature of a place we had never seen: for if we had, we should at all events have rushed upon the guard, and been, as the lesser evil, by our own choice cut to pieces.

Amongst the first

that entered, were myself, Messrs. Baillie, Jenks, Cooke, T. Coles, Ensign Scot, Revely, Law, Buchanan, &c. I got possession of the window nearest

the door, and took Messrs. Coles and Scot into the window with me, they being

both wounded (the first I believe mortally). The rest of the above mentioned

gentlemen were close round me. It was now about

Figure to yourself, my friend, if possible, the situation of a hundred and forty six wretches, exhausted by continual fatigue and action, thus crammed together in a cube of about eighteen feet, in a close sultry night, in Bengal, shut up to the eastward and southward (the only quarters from whence air could reach us) by dead walls, and by a wall and door to the north, open only to the westward by two windows, strongly barred with iron, from which we could receive scarce any the least circulation of fresh air.

What must ensue, appeared to me in lively and dreadful colours, the instant I cast my eyes around, and saw the size and situation of the room. Many unsuccessful attempts were made to force the door; for having nothing more than our hands to work with, and the door opening inward, all endeavours were vain and fruitless.

Conjectural View of the 'Black Hole,' with part of barrack, as seen from Interior of Verandahby S. de Wilde (Thacker, Spink & Co. Calcutta).

Observing every one giving way to the violence of passions, which I foresaw must be fatal to them, I requested silence might be preserved, whilst I spoke to them and in the most pathetic and moving terms which occurred, I begged and intreated, that as they had paid a ready obedience to me in the day, they would now for their own sakes, and the sakes of those who were dear to them, and were interested in the preservation of their lives, regard the advice I had to give them. I assured them, the return of day would give us air and liberty; urged to them, that the only chance we had left for sustaining this misfortune, and surviving the night, was preserving a calm mind and quiet resignation to our fate; entreating them to curb, as much as possible, every agitation of mind and body, as raving and giving loose to their passions could answer no purpose, but that of hastening their destruction.

This produced a short interval of peace, and gave me a few minutes for reflection: though even this pause was not a little disturbed by the cries and groans of the many wounded, and more particularly of my two companions in the window. Death, attended with the most cruel train of circumstances, I plainly perceived must prove our inevitable destiny. I had seen this common migration in too many shapes, and accustomed myself to think on the subject with too much propriety to be alarmed at the prospect, and indeed felt much more for my wretched companions than myself.Amongst the guards posted at the windows, I observed an old Jemmautadaar near me, who seemed to carry some compassion for us in his countenance; and indeed he was the only one of the many in his station, who discovered the least trace of humanity. I called him to me, and in the most persuasive terms I was capable, urged him to commiserate the sufferings he was a witness to, and pressed him to endeavour to get us separated, half in one place, and half in another; and that he should in the morning receive a thousand Rupees for this act of tenderness. He promised he would attempt it, and withdrew; but in a few minutes returned, and told me it was impossible. I then thought I had been deficient in my offer, and promised him two thousand. He withdrew a second time, but returned soon, and (with I believe much real pity and concern) told me, it was not practicable; that it could not be done but by the Suba's order, and that no one dared awake him.

During this interval, though their passions were less violent, their uneasiness increased. We had been but few minutes confined, before every one fell into a perspiration so profuse, you can form no idea of it. This consequently brought a raging thirst, which still increased, in proportion as the body was drained of moisture.

Various expedients were thought of to give the room more air. To obtain the former, it was moved to put off their clothes. This was approved as a happy motion, and in a few minutes I believe every man was stripped (myself, Mr. Court, and the two wounded gentlemen by me excepted). For a little time they flattered themselves with having gained a mighty advantage; every hat was put in motion, to produce a circulation of air; and Mr. Baillie proposed that every man should sit down on his hams. As they were truly in the situation of drowning wretches, no wonder they caught at every thing that bore a flattering appearance of saving them. This expedient was several times put in practice, and at each time many of the poor creatures, whose natural strength was less than others, or had been more exhausted, and could not immediately recover their legs, as others did, when the word was given to RISE, fell to rise no more; for they were instantly trod to death, or suffocated. When the whole body sat down, they were so closely wedged together, that they were obliged to use many efforts, before they could put themselves in motion to get up again.

Exterior view of the building which contained the Black Hole of Calcutta - as it would have appeared in 1756.

Before

Efforts were again made to force the door, but in vain. Many insults were used to the guard, to provoke them to fire in upon us (which as I learned afterwards, were carried to much greater lengths, when I was no more sensible of what was transacted). For my own part, I hitherto felt little pain or uneasiness, but what resulted from my anxiety for the sufferings of those within. By keeping my face between two of the bars, I obtained air enough to give my lungs easy play, though my perspiration was excessive, and thirst commencing. At this period, so strong an urinous volatile effluvia came from the prison, that I was not able to turn my head that way, for more than a few seconds at a time.

Now every body, excepting those situated in and near the windows, began to grow outrageous, and many delirious: Water, Water, became the general cry. And the old Jemmautadaar, before mentioned, taking pity on us, ordered the people to bring some skins of water, little dreaming, I believe, of its fatal effects, This is what I dreaded. I foresaw it would prove the ruin of the small chance left us, and essayed many times to speak to him privately to forbid its being brought; but the clamour was so loud, it became impossible. The water appeared. Words cannot paint to you the universal agitation and raving the sight of it threw us into. I had flattered myself that some, by preserving an equal temper of mind, might outlive the night; but now the reflection which gave me the greatest pain, was, that I saw no possibility of one escaping to tell the dismal tale.

Until the water came, I had myself not suffered much from thirst, which instantly grew excessive. We had no means of conveying it into the prison, but by hats forced through the bars; and thus myself and Messrs. Coles and Scot (notwithstanding the pains they suffered from their wounds) supplied them as fast as possible. But those, who had experienced intense thirst, or are acquainted with the cause and nature of this appetite, will be sufficiently sensible it could receive no more than a momentary alleviation; but the cause still subsisted. Though we brought full hats within the bars, there ensued such violent struggles, and frequent contests, to get at it, that before it reached the lips of anyone, there would be scarcely a small tea-cup full left in them. These supplies, like sprinkling water on fire, only served to feed and raise the flame.

Oh! My dear Sir, how shall I give you a conception of what I felt at the cries and ravings of those in the remoter parts of the prison, who could not entertain a probable hope of obtaining a drop, yet could not divest themselves of expectation, however unavailing! And others calling on me by tender considerations of friendship and affection, and who knew they were really dear to me. Think, if possible, what my heart must have suffered at seeing and hearing their distress, without having it in my power to relieve them; for the confusion now became general and horrid. Several quitted the other window (the only chance they had for life) to force their way to the water, and the throng and press upon the window was beyond bearing; many forced their passage from the further part of the room, pressed down those in their way, who had less strength, and trampled them to death.

Can it gain belief, that this scene of misery proved entertainment to the brutal wretches without? But so it was; and they took care to keep us supplied with water, that they might have the satisfaction of seeing us fight for it, as they phrased it, and held up lights to the bars, that they might lose no part of the inhuman diversion.

From about nine to near eleven, I sustained this cruel scene and painful situation, still supplying them with water, though my legs were almost broke with the weight against them. By this time I myself was very near pressed to death, and my two companions, with Mr. William Parker, (who forced himself into the window) were really so.

For a great while they preserved a respect and regard to me, more than indeed I could well expect, our circumstances considered; but now all distinction was lost. My friend Ballie, Messrs. Jenks, Ravely, Law, Buchanan, Simson, and several others, for whom I had no real esteem or affection, had for some time been dead at my feet, and were now trampled upon by every corporal and common soldier, who, by the help of more robust constitutions, had forced their way to the window, and held fast by the bars over me, till at last I became so pressed and wedged up, I was deprived of all motion.

Determined now to give everything up, I called to them, and begged, as the last instance of their regard, they would remove the pressure upon me, and permit me to retire out of the window, to die in quiet. They gave way; and with much difficulty I forced passage into the centre of the prison, where the throng was less by the many dead, (then I believe amounting to one third) and the numbers who flocked to the windows; for by this time they had water also at the other window.

In the Black-Hole there is a platform[14] corresponding with that in the barracks: I travelled over the dead, and repaired to the further end of it, just opposite the other window, and seated myself on the platform between Mr. Dumbleton and Capt. Stevenson, the former just then expiring. I was still happy in the same calmness of mind I had preserved the whole time; death I expected as unavoidable, and only lamented its slow approach, though the moment I quitted the window, my breathing grew short and painful.

Here my poor friend Mr. Edward Eyre came staggering over the dead to me, and with his usual coolness and good-nature, asked me how I did? But fell and expiredbefore I had time to make him a reply. I laid myself down on some of the dead behind me , on the platform; and recommending myself to heaven, had the comfort of thinking my sufferings could have no long duration.

My thirst grew now insupportable, and difficulty of breathing much increased; and I had not remained in this situation, I believe, ten minutes, when I was seized with a pain in my breast, and palpitation of my heart, both to the most exquisite degree. These roused me and obliged me to get up again; but still the pain, palpitation, thirst, and difficulties of breathing increased. I retained my senses notwithstanding, and the grief to see death not so near me as I hoped; but could no longer bear the pains I suffered without attempting a relief, which I knew fresh air would and could only give me; and by an effort of double the strength I ever before possessed, gained the third rank of it, with one hand seized a bar, and by that means gained the second, though I think there were at least six or seven ranks between me and the window.

In a few moments my pain, palpitation, and difficulty of breathing ceased; but my thirst continued intolerable. I called aloud for 'WATER FOR GOD'S SAKE:' I had been concluded dead; but as soon as they heard me amongst them, they had still respect and tenderness for me, to cry out, 'GIVE HIM WATER, GIVE HIM WATER!' nor would one of them at the window attempt to touch it until I had drank. But from the water I found no relief; my thirst was rather increased by it; so I determined to drink no more, but patiently wait the event; and kept my mouth moist from time to time by sucking the perspiration out of my shirt-sleeves, and catching the drops as they fell, like heavy rainfrom my head and face: you can hardly imagine how unhappy I was if any of them escaped my mouth.

I came into prison without coat or waistcoat; the season was too hot to bear the former, and the latter tempted the avarice of one of the guards, who robbed me of it when we were under the veranda. Whilst I was at this second window, I was observed by one of my miserable companions on the right of me, in the expedient of allaying my thirst by sucking my shirt-sleeve. He took the hint, and robbed me from time to time of a considerable amount of my store; though after I detected him, I had ever the address to begin on that sleeve first, when I thought my reservoirs were sufficiently replenished; and our mouths and noses often met in contest. This plunderer, I found afterwards, was a worthy young gentleman in the service, Mr. Lushington, one of the few who escaped from death, and since paid me the compliment of assuring me, he believed he owed his life to the many comfortable draughts he had from my sleeves. I mention this incident, as I think nothing can give you a more lively idea of the melancholy fate and distress we were reduced to. Before I hit upon this happy expedient, I had, in an ungovernable fit of thirst, attempted drinking my urine; but it was intensely bitter there was no enduring a second taste, whereas no Bristol water could be more soft or pleasant than what arose from perspiration.

By half an hour past eleven the much greater number of those living were in an outrageous delirium, and the others quite ungovernable; few retaining any calmness, but the ranks next to the windows. By what I had felt myself, I was fully sensible what those within suffered; but had only pity to bestow upon them, not then thinking how soon I should myself become a greater object of it.

They now found, that water, instead of relieving, rather heightened their uneasiness, and, 'AIR, AIR,'was the general cry. Every insult that could be devised against the guard, all the opprobrious names and abuse that the Suba, Monickchund[15], &c. could be loaded with, were repeated to provoke the guard to fire upon us, every man that could, rushing tumultuously towards the windows with eager hopes of meeting the first shot. Then a general prayer to heaven, to hasten the approach of the flames to the right and left of us, and put a period to our misery. But these failing, they whose strength and spirits were quite exhausted, laid themselves down and expired quietly upon their fellows: others who had yet some strength and vigour left, made a last effort for the windows, and several succeeded by leaping and scrambling over the backs and heads of those in the first ranks; and got hold of the bars, from which there was no removing them. Many to the right and left sunk with the violent pressure, and were soon suffocated; for now a stream arose from the living and the dead, which affected us in all its circumstances, as if we were forcibly held with our heads over a bowl full of strong volatile spirit of hartshorn, until suffocated; nor could the effluvia of the one be distinguished from the other, and frequently, when I was forced by the load upon my head and shoulders, to hold my face down, I was obliged, near as I was to the window, instantly to raise it again to escape suffocation.

I need not, my dear friend, ask your commiseration, when I tell you that in this plight, from half an hour past eleven till near two in the morning, I sustained the weight of a heavy man with his knees in my back and the pressure of his whole body on my head. A Dutchsergeant, who had taken a seat upon my shoulder, and a Topaz[16] bearing on my right; all which nothing could have enabled me long to support, but the props and pressure equally sustaining me all around. The two latter I frequently dislodged, by shifting my hold on the bars, and driving my knuckles into their ribs; but my friend above stuck fast, and as he held by two bars, was immovable.

When I had bore this conflict above an hour, with a train of wretched reflections, and seeing no glimpse of hope on which to found a prospect of relief, my spirits, resolution, and every sentiment of religion gave way, I found I was unable much longer to support this trial, and could not bear the dreadful thoughts of retiring into the inner part of the prison, where I had before suffered so much. Some infernal spirit, taking the advantage of this period, brought to my remembrance my having a small clasp penknife in my pocket, with which I determined instantly to open my arteries, and finish a system no longer to be borne. I had got it out, when heaven interposed, and restored me to fresh spirits and resolution, with an abhorrence of the act of cowardice I was just going to commit: I exerted anew my strength and fortitude; but repeated trials and efforts I made to dislodge the insufferable encumbrances upon me at last quite exhausted me, and towards two O’clock, finding I must quit the window, or sink where I was, I resolved on the former, having bore truly for the sake of others, infinitely more fore life than the best of it is worth.

In the rank close behind me was an officer of one of the ships, whose name was Carey, who had behaved with much bravery during the siege, (his wife, a fine woman though country-born, would not quit him, but accompanied him into the prison, and was one who survived). This poor wretch had been long raving for water and air; I told him I was determined to give up life, and recommended his gaining my station. On my quitting, he made a fruitless attempt to get my place; but the Dutchsergeant who sat on my shoulder supplanted him.

Poor Carey expressed his thankfulness, and said, he would give up life too; but it was with the utmost labour weforced our way from the window, (several in the inner ranks appearing to be dead standing.)[17] He laid himself down to die: and his death, I believe, was great, and I imagine, had not retired with me, I should never have been able to have forced my way.

I was at this time, sensible of no pain and little uneasiness: I can give you no better idea of my situation than by repeating my simile of the bowl of spirit of hartshorn. I found a stupor coming on apace, and laid myself down by that gallant old man, the reverend Mr. Jervas Bellamy, who lay dead with his son the lieutenant, hand in hand, near the southernmost wall of the prison.

When I had lain there some little time, I still had reflection enough to suffer some uneasiness in the thought, that I should be trampled upon, when dead, as I myself had done to others. With some difficulty I raised myself, and gained the platform a second time, where I presently lost all sensation: the last trace of sensibility that I have been able to recollect after his lying down, was my sash being uneasy about my waste, which I untied and threw from me.

Of what passed in this interval to the time of his resurrection from this hole of horrors, I can give you no account; and indeed, the particulars mentioned by some of the gentlemen who survived, (solely by the number of those dead, by which they gained a freer accession of air, and approach to the windows) were so excessively absurd and contradictory, as to convince me, very few of them retained their senses; or at least, lost them soon after they came into the open air, by the fever they carried out with them.

In my own escape from absolute death the hand of heaven was manifestly exerted: the manner takes as follows. When the day broke, and the gentlemen found that no entreaties could prevail to get the door opened, it occurred to one of them, (I think to Mr. Secretary Cooke) to make a search for me, in hopes I might have influence enough to gain a release from this scene of misery. Accordingly Messrs. Lushington and Walcot undertook the search, and by my shirt discovered me under the dead upon the platform. They took me from thence; and imagining I had some signs of life, brought me towards the window I had first possession of.

But as life was equally dear to every man, (and the stench arising from the dead bodies was grown intolerable) no one would give up his station in or near the window: so they were obliged to carry me back again. But soon after Captain Mills[18] (then captain of the company’s yacht) who was in possession of a seat in the window, had the humanity to offer to resign it. I was again brought by the same gentlemen, and placed in the window.

At this juncture the Suba, who had received an account of the havoc death had made amongst us, sent one of his Jemmautdaars to inquire if the chief survived. They showed me to him; and told him Holwellhad appearance of life remaining, and believed he might recover if the door was opened very soon. This answer being returned to the Suba, an order came immediately for their release, it being near six in the morning.

The fresh air in the window soon brought me to life; and a few minutes after the departure of the Jammautdaar, I was restored to my sight and senses. But oh! Sir, what words shall I adopt to tell you the whole that my soul suffered at reviewing the dreadful destruction around me? I will not attempt it; and indeed tears (a tribute I believe I shall ever pay to the remembrance to this scene, and to the memory of those brave and valuable men) stop my pen.

The little strength remaining amongst the most robust who survived, made it a difficult task to remove the dead piled up against the door; so that I believe it was more than twenty minutes before they obtained a passage out for one at a time.

I had soon reason to be convinced that the particular inquiry made after me did not result from any dictate of favour, humanity, or contrition; when I came out, I found myself in a high putrid fever, and not being able to stand, threw myself on the wet grass without the Veranda, when a message was brought me, signifying I must immediately attend the Suba. Not being capable of walking, they were obliged to support me under each arm; and on the way, one of the Jammautdaars told me, as a friend, to make full confession where the treasure was buried in the fort, or that in half an hour I should be shot from the mouth of a cannon[19]. The intimation gave me no manner of concern; for, at that juncture, I would have esteemed death the greatest favour the tyrant could have bestowed upon me.

Being brought into his presence, he soon observed the wretched plight Iwas in, and ordered a large folio volume, which lay on a heap of plunder, to be brought for me to sit on. I endeavoured two or three times to speak, but my tongue was dry and without motion. He ordered me water. As soon as I got speech, I began to recount the dismal catastrophe of my miserable companions. But I was stopped short, with telling me, that he was well informed of great treasure being buried or secreted in the fort, and that I was privy to it; and if I expected favour, must discover it.

I urged everything I could to convince the Suba there was no truth in the information; for that if any such thing had been done, it was without my knowledge. He reminded me of his repeated assurance to me, the day before; but he resumed the subject of the treasure, and all I could say seemed to gain no credit with him. I was ordered prisoner under Mhir Muddon, General of the Household Troops.

Amongst the guards which carried me from the Suba, one bore a large Moratter battle-axe, which gave rise he imagined, to Mr. Secretary Cooke’s belief and report to the fleet, that he (Mr Cooke) saw him carried out with the edge of the axe towards me, to have my head struck off. This I believed is the only account you will have of me, until I bring you a better one myself. But to resume the subject: He was ordered to the camp of Mhir Muddon’s quarters within the outward ditch, something short ofOmychund’s garden (which is above three miles from the fort) and with him Messieurs Court, Walcot, and Burdet. The rest, who survived the fatal night, gained their liberty except Mrs. Carey, who was too young and handsome. The dead bodies were promiscuously thrown into the ditch of their unfinished ravelin, and covered with the earth.

The site of the Black Hole as it appeared about one hundred years ago. An approximate area of the room seems to have been cordoned off with railings: a quaint touch with great tourist potential, yet a subtlety that is completely lost on West Bengal’s authorities who even demolished William Makepeace Thackeray’s birthplace to build an ugly block of flats (1973). The site is now merely part of a sidewalk although the plaque can still be seen (B & L T Co.).

Holwellwas then transferred out of Calcutta as a prisoner and taken to Bengal's erstwhile capital:

We were conveyed in a Hackery[20] to the camp the 21stof June, in the morning, and soon loaded with fetters, and stowed all four in a seypoy’s tent, about four feet long, three wide, and about three high; so that they were half in, half out : All night it rained severely. Dismal as this was, it appeared a paradise compared with their lodging the previous night. Here I became covered from head to foot with large painful boils, the first symptom of my recovery; for until these appeared, my fever did not leave me.

On the morning of the 22nd, they marched us to town in their fetters, under the scorching beam of an intense hot sun, and lodged us at the Dock-head in the open small Veranda, fronting the river, where they had a strong guard over us, commanded by Bundo Singh Hazary, an officer under Mhir Muddon. Here the other gentlemen broke out likewise in boils all over their bodies (a happy circumstance, which, as I afterwards learned, attended every one who came out of the Black Hole.)

In short (Sir), though our distresses in this situation, covered with tormenting boils, and loaded with irons, will be thought, and doubtless were, very deplorable; yet the grateful consideration of our being so providentially a remnant of the saved, made everything else appear light to us. Their rice and water-diet, designed as a grievance to us, was certainly our preservation: for, could we (circumstanced as we were) have indulged in flesh and wine, we would have died beyond all doubt.

Some days later the despondent and hollow-eyed prisonersarrived in Murshidabad('Muxadabad') and virtually lived from handouts delivered to them by sympathetic Dutchmen and Frenchmen.[21] In his letter Holwelllaments:

This march I will freely confess to you, drew tears of disdain and anguish of hear from me; thus to be led like a felon, a spectacle to theinhabitants of this populous city ! My soul could not support itself with any degree of patience; the pain too arising from my boils, and inflammation of my leg, added not a little, I believe, to the depression of my spirits.

Here we had a guard of Moors, [Muslims] placed on one side of us, and a guard of Gentoos [Hindus] on the other; and being destined to remain in this place of purgatory, until the Suba returned to the city, I can give you no idea of our sufferings. The immense crowd of spectators, who came from all quarters of the city to satisfy their curiosity, so blocked us up from morning till night, that I may truly say we narrowly escaped a second suffocation, the weather proving exceedingly sultry.

The first night after our arrival in the stable, I was attacked by a fever; and that night and the next day, the inflammation of my leg and thigh greatly increased: but all terminated the second night in a regular fit of the gout in my right-foot and ankle; the first and last fit of this kind I ever had. How my irons agreed with this new visitor I leave you to judge; for I could not by any entreaty obtain liberty for so much as that poor leg.

As the vengeful English closed in on Siraj, Holwelland his companions were in time handed back to their compatriots, whereupon he wrote the above letter, of which the majority has been quoted.

---

How little were the strange issues of these dismal events foreseen. Intrepid Britons soon came with Admiral Watson and Colonel Clivefrom Madras, to the succour of those of their countrymen, who had escaped destruction. Victory attended the little army whithersoever it advanced, and before the anniversary of the unhappy siege came round, Calcutta had been triumphantly re-taken, the battle of Plassey had been won, and the throne of the Nawab was occupied by a partisan of the English. By those who had been his own creatures, the fugitive tyrant was put to death, while the British obtained that firm footing and that arm of power in Bengal, which speedily led to their acknowledged supremacy there. In short, the foundations had been laid of that great Indian empire, whose growth has been as marvellous as its beginning.

(Carey)

---

Sirajud Dowla

Fact or Fiction?

In 1915, J. H. Little wrote an article entitled, 'The Black Hole - The Question of Holwell's Veracity,'in which he outlined some alleged flaws in Holwell's story. He claimed that Holwellwas an unreliable witness and stated that the incident was either fictitious or had been exaggerated. This concept gained much appeal amongst leftists and Indian nationalists who seized upon the idea that Holwell, the British hero, could have been a manipulative villain. As journalists often say - a story too good to check!

Over the last fifty years the debate has degenerated yet further, with many old inaccuracies and half truths being regurgitated and quoted as incontrovertible facts. So why such frantic and often extremely inept attempts to discredit Holwell's story?

The problem is that the Black Hole incident was another fair excuse for Sir Robert Cliveto attack Bengal. To ascribe fairness to Clive's rampage is an extremely discomforting concept - yet an inescapable one based on the available evidence. It is therefore more befitting to our emotional needs to imagine that the incident never occurred andcreate a conspiracy theory based on nothing in particular and a strong desire for Holwell's account not to be true.